Post–Cardiac Arrest Syndrome in South Africa: Evidence-Based Post-ROSC Management and Why ACLS Training Matters

A 56-year-old male collapses at home in a peri-urban area of KwaZulu-Natal. His wife initiates CPR after being guided by a call-taker. A private ambulance arrives within eight minutes. The patient is found in ventricular fibrillation. After two shocks, high-quality CPR, and appropriate drug therapy, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is achieved.

The patient is intubated, ventilated, and transported to the nearest emergency centre. En route, blood pressure is borderline, oxygen saturation reads 100% on high-flow oxygen, and capillary glucose is elevated. On arrival, the patient remains comatose.

Within the next few hours, hypotension develops, metabolic acidosis worsens, urine output drops, and an echocardiogram reveals global left ventricular dysfunction. By the following day, fever and inflammatory markers rise, and neurological prognosis becomes uncertain.

This is post-cardiac arrest syndrome (PCAS), a condition South African healthcare providers encounter frequently, yet one that remains inconsistently recognised and managed across prehospital, emergency centre, and ICU settings.

Understanding and managing PCAS is a core competency of Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) and a critical determinant of survival beyond ROSC.

Incidence in the South African context

In low-resource settings such as South Africa, pooled international data show that although nearly 30% of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) patients achieve ROSC, fewer than 9% survive to hospital discharge, underscoring the critical role of post-resuscitation care. While comprehensive national cardiac arrest registries remain limited, local experience mirrors international data: survival to hospital discharge after ROSC remains low, particularly following OHCA (Stassen et al., 2022).

In South Africa, outcomes are further influenced by:

- Variable response times between urban and rural EMS systems

- Differences in access to advanced prehospital interventions

- Differences in access to definitive care (private vs public healthcare facilities)

- Inconsistent post-cardiac arrest protocols between facilities

These realities highlight a critical point: post-resuscitation care, not CPR quality alone, determines survival. Facilities and clinicians with structured post–cardiac arrest pathways demonstrate better outcomes, reinforcing the importance of advanced training, protocolised care, and ACLS competency (Nolan et al., 2008).

Pathophysiology: A whole-body problem after ROSC

Post-cardiac arrest syndrome represents a global ischemia-reperfusion injury, unique in its severity and complexity. During cardiac arrest, total cessation of blood flow results in widespread cellular injury. When circulation is restored, reperfusion initiates additional inflammatory and metabolic cascades that further damage organs.

ILCOR defines four interrelated components of PCAS:

- Post-cardiac arrest brain injury

- Post-cardiac arrest myocardial dysfunction

- Systemic ischemia/reperfusion response

- Persistent precipitating pathology

In the South African setting, where prolonged downtime, delayed defibrillation, and extended transport times are not uncommon, PCAS often dominates the clinical picture after ROSC. ACLS-trained providers are expected to recognise and manage these processes early (Neumar et al., 2008).

Post-Cardiac Arrest Brain Injury: The Primary Determinant of Outcome

Neurological injury is the leading cause of death in patients who survive initial resuscitation. The brain’s vulnerability to ischemia and reperfusion makes it particularly susceptible to secondary injury in the hours and days following ROSC.

Mechanisms include:

- Excitotoxic neurotransmitter release

- Calcium influx and mitochondrial dysfunction

- Free radical production

- Activation of apoptotic pathways

These processes evolve over time, creating a therapeutic window during which appropriate management can influence outcome.

South African clinical relevance

In local practice, secondary brain injury is commonly exacerbated by:

- Hypotension during transport or early ICU admission

- Hyperoxia from prolonged high-flow oxygen use

- Hypoxia from inadequate oxygenation

- Delayed temperature control

- Hyperglycaemia from poor glucose control

- Poor seizure recognition in sedated or paralysed patients

Clinical manifestations include coma, seizures, myoclonus, cognitive impairment, Cortical stroke, Spinal stroke, persistent vegetative states, and brain death (Neumar et al.,2008).

ACLS training explicitly addresses prevention of secondary neurological injury, including oxygen titration, haemodynamic optimisation, temperature management, glucose control, and seizure recognition, skills essential in South African EMS, emergency centres, and ICUs.

Post-Cardiac Arrest Myocardial Dysfunction

Post-cardiac arrest myocardial dysfunction is common and frequently misunderstood. Rather than representing permanent myocardial damage, it is often a reversible global myocardial stunning phenomenon.

Key features include:

- Reduced cardiac output

- Hypotension

- Tachyarrhythmias

- Elevated filling pressures

Studies show that ventricular function often recovers within 24–72 hours in survivors, provided appropriate support is given (Neumar et al.,2008).

Local implications

In South African practice, this dysfunction may be misinterpreted as:

- Ongoing myocardial infarction

- Fluid overload

- Futility

ACLS-trained clinicians are better equipped to:

- Recognise myocardial stunning

- Support circulation with fluids and inotropes when appropriate

- Advocate for early coronary reperfusion when indicated

This distinction is critical to avoid premature withdrawal of care.

Systemic Ischaemia/Reperfusion Response After Cardiac Arrest

Cardiac arrest produces the most extreme form of shock. Following ROSC, a systemic inflammatory response develops, similar to sepsis.

This response includes:

- Vasodilation and hypotension

- Capillary leak

- Coagulopathy

- Impaired oxygen utilisation

- Increased susceptibility to infection

In South Africa, where the infectious disease burden is already high, this inflammatory state significantly increases the risk of pneumonia and sepsis. Early recognition and aggressive management of this response are core ACLS post-ROSC principles (Nolan et al., 2008).

Persistent Precipitating Pathology: Treating the Cause, Not Just the Arrest

Post-cardiac arrest syndrome does not occur in isolation. The underlying cause of arrest, such as acute coronary syndrome, hypoxia, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, trauma, or toxicological emergencies, often persists after ROSC.

In South Africa, delayed diagnosis and referral can significantly worsen outcomes. ACLS training reinforces the need for:

- Early identification of reversible causes

- Integration of post-arrest stabilisation with definitive care

- Clear communication during interfacility transfer

Failure to address the precipitating pathology undermines even the best post-resuscitation support.

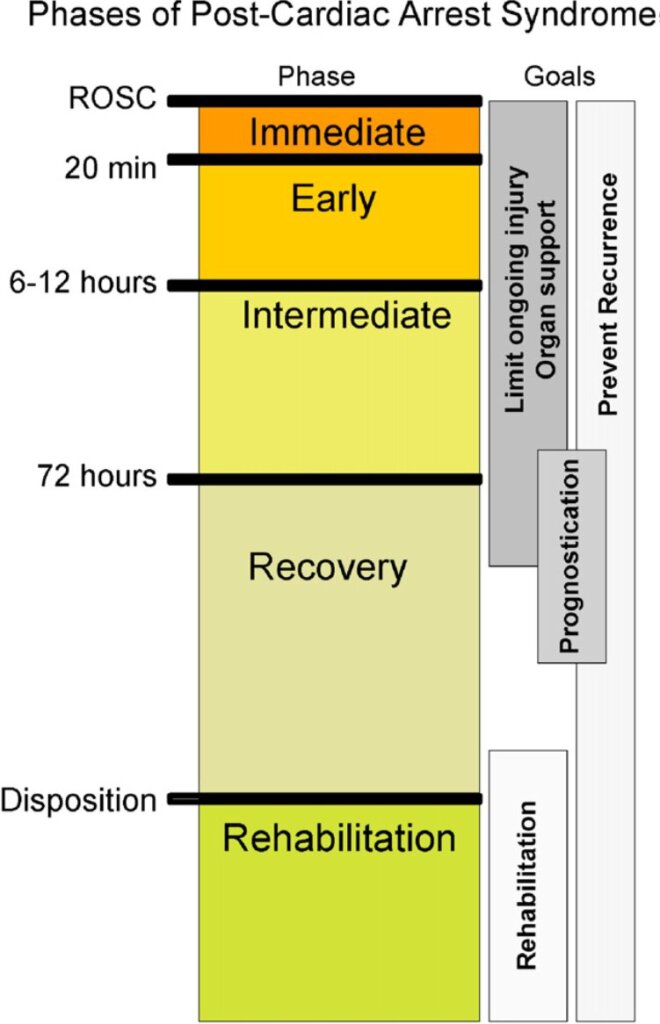

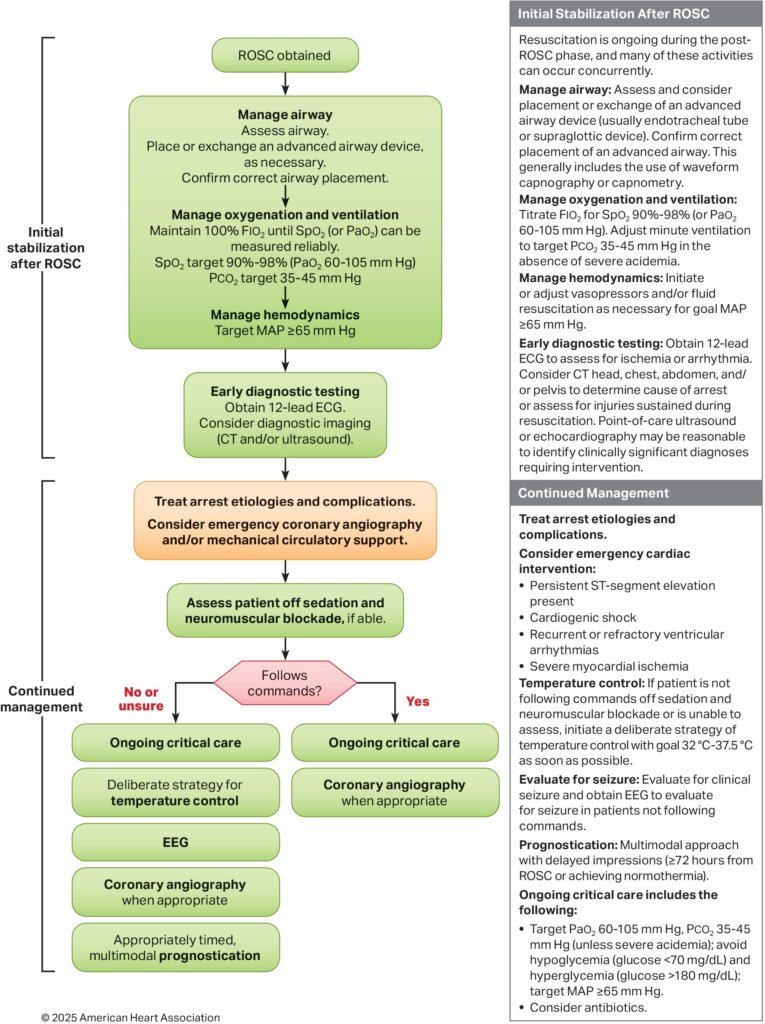

Evidence-Based Therapeutic Strategies: From ROSC to Recovery

Managing PCAS requires a structured, multidisciplinary approach, regardless of whether care occurs in EMS, emergency centres, or ICUs. The following content is based on recommendations from Part 11: Post–Cardiac Arrest Care: 2025 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care by (Hirsch et al., 2025

The management of PCAS is guided by four overarching goals:

- Prevent secondary brain injury

- Support myocardial recovery and systemic perfusion

- Identify and treat the cause of cardiac arrest

- Avoid iatrogenic harm while allowing time for recovery and prognostication

Achieving these goals requires active intervention. Passive observation after ROSC is associated with poor outcomes.

Oxygenation after cardiac arrest: Avoiding hypoxia and hyperoxia

Immediately after ROSC, high-concentration oxygen is appropriate while oxygenation is being assessed. However, prolonged exposure to hyperoxia is harmful.

Recommended approach

- Use 100% oxygen initially until reliable oxygen saturation or arterial oxygen measurements are available.

- Once monitoring is reliable, titrate FiO₂ to maintain:

- SpO₂ 90–98%

- PaO₂ approximately 60–105 mmHg

Why this matters

- Hypoxemia worsens ischemic injury to the brain and myocardium.

- Hyperoxemia increases oxidative stress through excess reactive oxygen species, exacerbating reperfusion injury.

Clinicians must also be aware that pulse oximetry may be less accurate in patients with darker skin pigmentation, potentially masking hypoxemia. In critically ill post-arrest patients, arterial blood gas analysis should be used whenever feasible to guide oxygen therapy

Ventilation and carbon dioxide control

Ventilation management after cardiac arrest is not simply about achieving “normal” blood gases—it is about protecting cerebral perfusion.

Target values

- Maintain PaCO₂ in the normal physiologic range (35–45 mmHg) in comatose patients after ROSC.

Physiological rationale

- Hypocapnia causes cerebral vasoconstriction, reducing cerebral blood flow and worsening ischemia.

- Hypercapnia causes cerebral vasodilation, increasing intracranial pressure and potentially worsening cerebral edema.

Because end-tidal CO₂ measurements may be unreliable in low-flow states, arterial blood gases should be obtained in mechanically ventilated post-arrest patients to confirm PaCO₂ targets whenever possible

Blood pressure and perfusion targets

Hypotension after ROSC is common and strongly associated with poor neurological outcomes.

Minimum target

- Maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65 mmHg

Individualised perfusion

While a MAP of 65 mmHg is a minimum threshold, optimal blood pressure varies between patients. Factors influencing targets include:

- Severity of myocardial dysfunction

- Pre-arrest baseline blood pressure

- Degree of cerebral autoregulation impairment

- Ongoing shock physiology

Because cerebral autoregulation is often impaired after cardiac arrest, the brain may be pressure-dependent, requiring higher perfusion pressures to maintain adequate blood flow. Early and continuous haemodynamic optimisation is therefore central to PCAS management

Vasopressors and inotropic support

Up to 75% of post–cardiac arrest patients require vasopressors to maintain adequate perfusion.

Shock phenotypes after cardiac arrest

Post-arrest shock is dynamic and may evolve through phases:

- Early cardiogenic shock from myocardial stunning

- Later vasodilatory shock due to systemic inflammatory vasoplegia

- Mixed shock states requiring tailored therapy

Principles of vasopressor use

- Select agents based on the dominant physiology (low output vs vasodilation).

- Titrate to achieve perfusion targets rather than fixed doses.

- Monitor closely for adverse effects such as arrhythmias and tissue ischemia.

Vasoactive support should be reassessed frequently, as myocardial function often improves within 24–72 hours if adequate support is provided

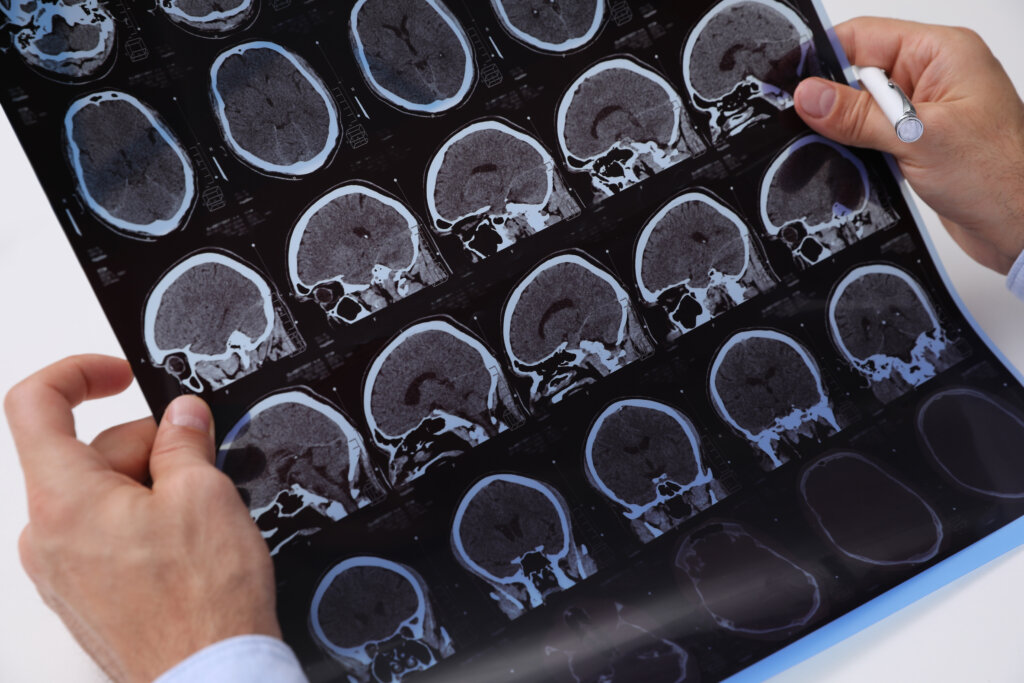

Diagnostic evaluation after ROSC

Post–cardiac arrest management must include active investigation of the cause of arrest and complications of resuscitation.

Core diagnostic studies

- 12-lead ECG as soon as feasible in all patients

- Echocardiography or point-of-care ultrasound to assess ventricular function and exclude mechanical causes

- CT imaging (head-to-pelvis when appropriate) to investigate:

- Intracranial pathology

- Pulmonary embolism

- Aortic pathology

- Traumatic complications of CPR

No single test is sufficient on its own. Diagnostic strategies must be guided by clinical context, recognising that abnormal findings are common but not always diagnostic or actionable

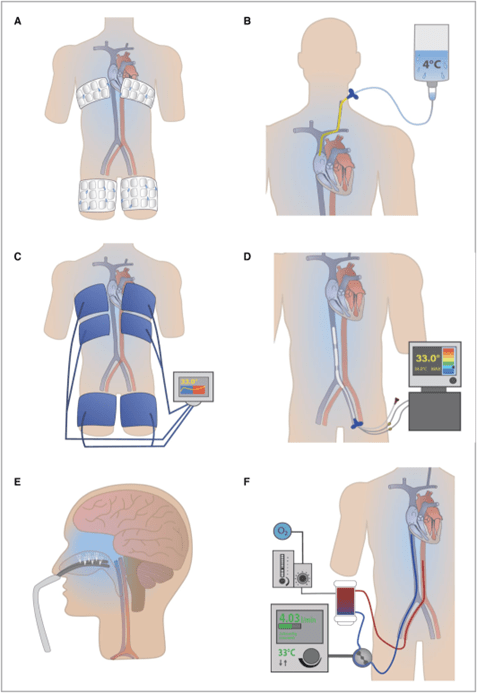

Temperature control and fever prevention

Temperature management remains a cornerstone of post–cardiac arrest care.

Current approach

- Active temperature control, targeting either:

- Controlled hypothermia or

- Strict normothermia with aggressive fever prevention

Recent evidence indicates that fever prevention is critical, regardless of whether hypothermia is employed. Fever after cardiac arrest is consistently associated with worse neurological outcomes.

Key principles

- Avoid uncontrolled hyperthermia

- Initiate temperature control early

- Maintain consistency throughout the active management period

Temperature control should be viewed as a continuous process, not a single intervention

Glucose control and metabolic management

Hyperglycemia is common after cardiac arrest and is associated with worse neurological outcomes.

Management considerations

- Avoid severe hyperglycemia

- Avoid hypoglycemia

- Use controlled insulin therapy where appropriate

Although tight glucose control has not consistently shown benefit, uncontrolled hyperglycemia contributes to secondary brain injury and should be actively managed as part of comprehensive PCAS care

Infection prevention and empiric therapies

Patients are at high risk of pneumonia after cardiac arrest due to:

- Aspiration during arrest

- Reduced airway reflexes

- Prolonged mechanical ventilation

While routine empiric antibiotics are not universally indicated, early identification and treatment of infection is essential. Decisions regarding antibiotics should be individualised and based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings

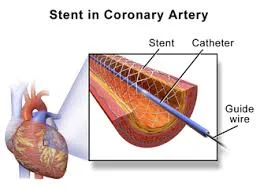

Coronary angiography and PCI

Coronary artery disease is identified in up to two-thirds of OHCA patients with a presumed cardiac etiology, with acute culprit lesions in approximately one-third.

Key considerations

- PCI improves outcomes by stabilising hemodynamics and preventing recurrent arrhythmias

- Early angiography is associated with improved survival in selected patients

- Evidence is strongest for patients with:

- STEMI

- Shockable rhythms

- Ongoing ischemia or instability

Clinical decision-making must balance the potential benefit of revascularisation against the competing risk of severe hypoxic-ischemic brain injury

Mechanical circulatory support (MCS)

Temporary mechanical circulatory support may be lifesaving in refractory cardiogenic shock.

Available options

- Intra-aortic balloon pump

- Percutaneous ventricular assist devices

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)

Role in PCAS

MCS can:

- Stabilise circulation

- Allow myocardial recovery

- Provide time for neurological assessment and prognostication

These benefits must be weighed against risks such as bleeding, limb ischemia, and infection. MCS is best utilised within structured systems with expertise and clear selection criteria

Advanced neuromonitoring

Conventional monitoring may fail to detect evolving secondary brain injury.

Advanced neuromonitoring modalities

- Intracranial pressure monitoring

- Brain tissue oxygenation (PbtO₂)

- Jugular venous oxygen saturation

- Continuous EEG

- Cerebral autoregulation indices

These tools allow physiology-guided interventions, though their use remains limited by resource availability and a lack of definitive outcome data in cardiac arrest populations

Seizures, status epilepticus, and myoclonus

Incidence

- Seizures or status epilepticus occur in 10–35% of comatose post-arrest patients.

- Myoclonus occurs in 18–34% of patients.

Management principles

- Clinical examination alone is insufficient—EEG monitoring is required.

- Treat seizures to reduce cerebral metabolic demand.

- Recognise that some patients with seizures or myoclonus can still achieve meaningful recovery.

Myoclonus may interfere with ventilation and care even when not epileptic and often requires symptomatic management

Allowing time for recovery and prognostication

One of the most important principles in PCAS management is avoiding premature prognostication. Neurological recovery after hypoxic-ischemic injury evolves over days, not hours.

Early withdrawal of care based on incomplete information risks creating a self-fulfilling poor outcome. Structured PCAS management exists precisely to buy time for recovery.

The management of post–cardiac arrest syndrome is active, complex, and resource-intensive—but it is also where survival and neurological outcome are decided. ROSC alone does not save lives. Thoughtful, evidence-based post-arrest care does.

Modern PCAS management requires:

- Precision in oxygenation and ventilation

- Vigilant hemodynamic support

- Temperature and metabolic control

- Early identification of reversible pathology

- Neurological protection and monitoring

- Multidisciplinary coordination

Clinicians trained in advanced life support and post–cardiac arrest care are best positioned to implement these strategies effectively. When delivered consistently, post-cardiac arrest management transforms ROSC from a transient victory into a meaningful chance at recovery.

Why ACLS Training Matters in South Africa | HSTCSA

In South Africa’s healthcare environment — characterised by variable resources, long transport times, and diverse scopes of practice — ACLS training provides a shared, evidence-based framework for post-cardiac arrest care.

Through HSTCSA’s ACLS training, healthcare professionals learn to:

- Recognise post–cardiac arrest syndrome early

- Prevent secondary brain and myocardial injury

- Implement structured post-ROSC management

- Improve neurological and survival outcomes

ROSC is not the endpoint of resuscitation. Survival with meaningful neurological recovery is the goal.

Clinicians managing post-cardiac arrest syndrome should be trained in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) to apply structured post-ROSC care. Attending an ACLS course with HSTCSA ensures providers are prepared not only to restart the heart — but to guide patients through the most vulnerable phase of their recovery using current AHA-aligned best practice.

References

- Hirsch, K.G., et al. (2025) Part 11: Post–Cardiac Arrest Care: 2025 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 152(Suppl 2), pp. S673–S718. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001375

- Neumar, R.W., et al. (2008) Post–cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. Circulation, 118(23), pp. 2452–2483. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190652

- Yan, S., et al. (2020) The global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients who received cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care, 24, Article 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-2773-2

- Jozwiak, M., et al. (2020) Post-resuscitation shock: Recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Annals of Intensive Care, 10, Article 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-020-00788-z

- Stassen, W., et al. (2022) Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in the City of Cape Town metropole of the Western Cape province of South Africa: A spatio-temporal analysis. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 33(5), pp. 260–266. https://doi.org/10.5830/CVJA-2022-019

- Lazzarin, T., et al. (2023) Post-cardiac arrest: Mechanisms, management, and future perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(1), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12010259

- Kang, Y. (2019) Management of post-cardiac arrest syndrome. Acute and Critical Care, 34(3), pp. 173–178. https://doi.org/10.4266/acc.2019.00654

- Nolan, J.P., et al. (2008) Post-cardiac arrest syndrome: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prognostication. Resuscitation, 79(3), pp. 350–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.09.017