The 2025 AHA Guidelines: Elevating Basic Life Support for Better Survival

DISCLAIMER

This blog contains discussions and general information about medical emergencies and other health topics. The information in this blog and in other related resources is not meant to be medical advice, and it should not be taken as such. The information contained in this blog should not be used in place of a medical doctor’s advice or treatment. If you or someone else has a medical concern, you should talk to your doctor or seek out other professional medical care. The opinions and views on this blog and website have no connection to those of any school, hospital, medical facility, or other organization.

Resources

Highlights of the 2025 American Heart Association Guidelines

A New Era of Evidence-Based Resuscitation

On October 22, 2025, the American Heart Association (AHA) released its most comprehensive update yet to the Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC).

This update reflects the latest scientific evidence from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) and represents a paradigm shift toward integrated systems of care, team-based resuscitation, and survivorship.

For clinicians, paramedics, and instructors, the 2025 guidelines redefine how we recognize, respond to, and recover from cardiac arrest — reinforcing the importance of quality, coordination, and continuous improvement in every link of the Chain of Survival.

If you’re a healthcare provider in South Africa, you can now align your clinical skills with these latest standards through our Basic Life Support (BLS) for Healthcare Providers Course — accredited and delivered by the Health & Safety Training Centre of South Africa (HSTCSA).

1. Adult Basic Life Support (BLS) 2025 — Back to the Core

The 2025 AHA Basic Life Support Guidelines place renewed focus on high-quality, evidence-driven CPR at every stage of care.

Key Updates in Recognition and Response

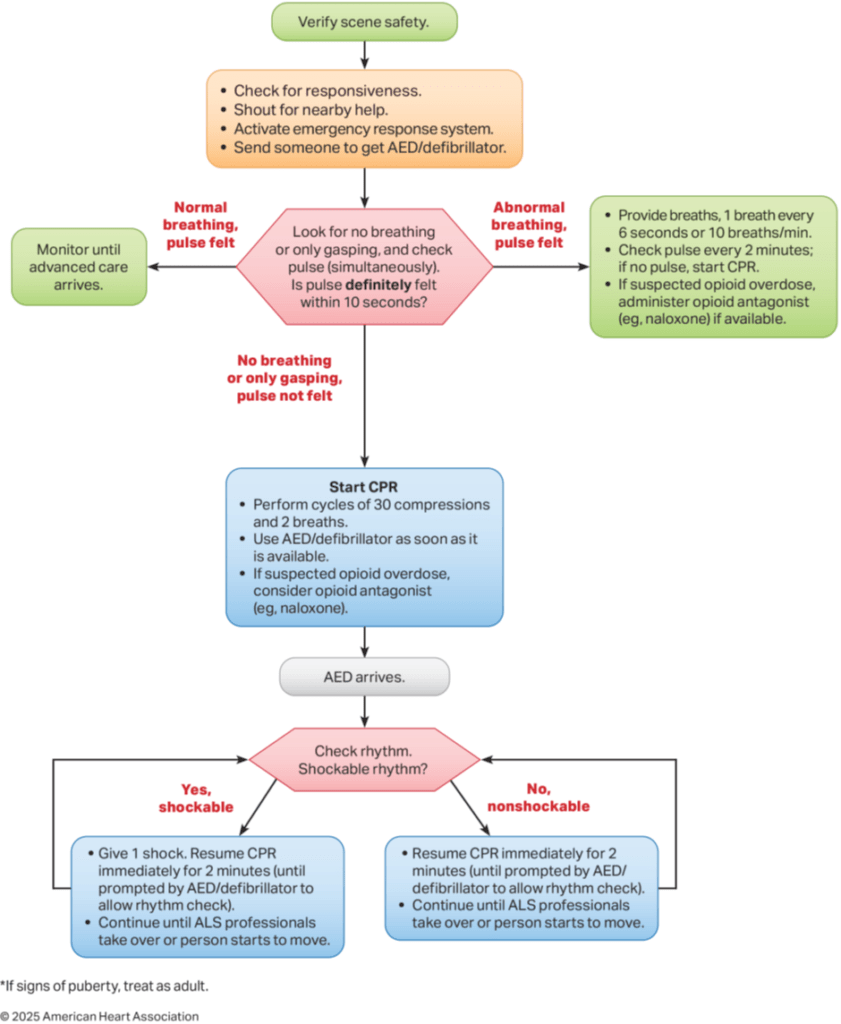

The AHA now includes three refined BLS algorithms:

- Adult BLS for Healthcare Providers — integrates opioid antagonist (naloxone) use during both respiratory and cardiac arrest.

- Adult BLS for Lay Rescuers — simplified version emphasizing early CPR and EMS activation.

- Foreign-Body Airway Obstruction (FBAO) — standardizes 5 back blows + 5 thrusts for choking relief.

Recognition of Cardiac Arrest

Accurate recognition remains one of the most critical yet challenging steps in resuscitation — especially in the out-of-hospital environment.

For Lay Rescuers:

If an adult is unresponsive and not breathing normally (only gasping or showing irregular breaths), cardiac arrest should be assumed immediately and CPR should be started without checking for a pulse.

For Healthcare Professionals:

When encountering an unresponsive, abnormally breathing patient, clinicians should perform a brief pulse check lasting no longer than 10 seconds. If no definite pulse is detected within that time, cardiac arrest should be assumed and compressions should begin promptly.

2. Initiation of Resuscitation

Immediate action remains critical. The AHA 2025 update clarifies differences between trained lay rescuers and professional responders.

| Aspect | Lay Rescuers | Health Care Professionals |

| Initial Action | Activate emergency response system and start compressions immediately. | Begin CPR with chest compressions using the C–A–B sequence. |

| Sequence of CPR | Emphasis on Hands-Only CPR for untrained rescuers. Trained rescuers may add breaths. | Always use Compressions + Ventilations once compressions begin. |

| Ventilations | Optional — recommended only if rescuer is trained and willing. | Required — performed via mouth-to-mask or bag-mask device. |

| Cause-Specific Approach | Same for all causes — simplified algorithm for public use. | Tailored approach: may adjust based on arrest cause (e.g., asphyxial vs. cardiac). |

| Use of Equipment | Limited to AED use and basic protective gear. | Uses airway adjuncts, bag-mask devices, and oxygen if available. |

| PPE Use | Encouraged if available but must not delay CPR. | Expected standard practice when performing resuscitation. |

| System Activation | May use speakerphone to call EMS while performing CPR. | Works within coordinated team response or activates code system. |

| Training Level | Varies — can range from untrained to CPR-certified community members. | Advanced knowledge of anatomy, physiology, and airway management. |

| Primary Goal | Activate the emergency response, Initiate compressions quickly and maintain blood flow until EMS arrives. Provide early defibrillation if an AED becomes available | Deliver high-quality, integrated resuscitation (compressions + ventilations) for ROSC. |

Clinical Insight:

Lay rescuers are the first critical link in the chain, while healthcare professionals integrate advanced airway and oxygenation strategies for better outcomes.

Opening the Airway

Effective airway management is a cornerstone of Basic Life Support (BLS), ensuring that ventilation can be delivered safely and efficiently to unresponsive adults. The 2025 AHA Guidelines refine prior recommendations by clarifying when and how airway manoeuvres and adjuncts should be used — and when they should be avoided.

| Clinical Situation | Recommended Technique | Key Points / Considerations |

| Unresponsive adult (no trauma suspected) | Head Tilt–Chin Lift | Preferred airway-opening manoeuvre for all unresponsive adults.- Safe and effective when cervical spine injury is not suspected.- Standard for both healthcare providers and trained lay rescuers. |

| Unconscious adult (no gag or cough reflex) | Airway Adjuncts (OPA or NPA) | – Reasonable to use to maintain airway patency and facilitate ventilation. – OPA preferred in patients with suspected basal skull fracture or coagulopathy (avoid NPA) – Avoid OPA if gag reflex is present. |

| Routine Cricoid Pressure | Not Recommended | – No proven benefit; may hinder ventilation during bag-mask use. – Should not be applied routinely during cardiac arrest. |

| Head or Neck Trauma (suspected cervical spine injury) | Jaw Thrust (without head extension) | – First-line technique for trained rescuers. – Minimizes neck movement while opening the airway. – Use with airway adjuncts if available. |

| Head or Neck Trauma – Airway remains obstructed | Head Tilt–Chin Lift (as backup) | – If airway cannot be opened with jaw thrust and adjuncts, use gentle head tilt–chin lift. – Prioritize oxygenation and ventilation — survival takes precedence over spinal motion restriction. |

| Head or Neck Trauma – Lay Rescuers | Do NOT use Rigid Cervical Devices | – Lay rescuers should avoid rigid collars or immobilization devices. – Improper use by untrained individuals can worsen injury or delay resuscitation. |

Metrics for High-Quality CPR

Positioning and Location During Resuscitation

Delivering high-quality chest compressions remains the foundation of successful resuscitation. The 2025 AHA Guidelines reinforce that optimal outcomes depend on precise rescuer positioning, patient placement, and compression technique — all designed to maximize circulation during cardiac arrest.

2025 AHA Recommendations for Positioning and Location During CPR

| Recommendation | Best Practice Summary | Rationale / Clinical Insight |

| Patient Level Relative to Rescuer | The patient’s torso should be positioned at approximately the level of the rescuer’s knees whenever possible. | Optimizes compression angle and force generation, reducing rescuer fatigue while maintaining consistent depth. |

| Hand Placement | Place the heel of one hand on the center of the chest (lower half to lower third of the sternum), with the other hand on top, fingers interlaced. | Ensures proper pressure over the heart and reduces risk of rib fractures or ineffective compressions. |

| Resuscitation Location | Perform CPR where the patient is found, provided compressions can be delivered safely and effectively. | Avoids time loss associated with unnecessary patient movement before starting compressions. |

| Surface and Position | Prefer a firm surface with the patient in the supine position, as long as positioning does not delay chest compressions. | A firm surface improves compression depth and cardiac output compared with a soft bed or stretcher. |

| Dominant Hand Placement | Rescuers may use their dominant hand on the sternum for comfort and improved control during compressions. | Enhances mechanical advantage and consistency in compression depth, especially during prolonged efforts. |

| Prone Position Arrests | When cardiac arrest occurs with the patient in the prone position, it is preferable to turn the patient supine before starting compressions. If repositioning is unsafe, prone CPR may be performed as an alternative. | Allows flexibility in critical care or surgical settings where patient repositioning is difficult. |

Clinical Insight

The success of CPR depends not only on what rescuers do, but also on how they position themselves and the patient. The 2025 update emphasizes ergonomics and efficiency — maintaining proper rescuer posture, using body weight rather than arm strength, and minimizing interruptions to compressions.

Performing CPR where the patient collapses prevents unnecessary delays, and ensuring a firm, stable surface enhances perfusion by improving compression depth.

For special scenarios such as cardiac arrest in the prone position (common in surgical or ICU patients), rescuers are now advised to attempt supine repositioning when feasible — but if that’s not possible, prone CPR is acceptable and supported by growing clinical evidence.

Chest Compression Fraction and Pauses

Delivering continuous, high-quality chest compressions is one of the most effective ways to improve survival from cardiac arrest. The 2025 AHA Guidelines emphasize minimizing any interruptions during CPR to maintain adequate coronary and cerebral perfusion pressure — the key determinants of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).

Even brief pauses in compressions can cause a rapid drop in perfusion pressure, reducing the likelihood of successful defibrillation and ROSC. Therefore, the focus is on maximizing compression fraction — the percentage of total resuscitation time spent performing chest compressions.

Key Recommendations for Minimizing Interruptions

| Focus Area | Best Practice Summary |

| Pre-shock and Post-shock Pauses | Keep pauses before and after defibrillation as short as possible. Resume compressions immediately after shock delivery instead of checking the rhythm first. |

| Pulse and Rhythm Checks | During rhythm analysis, limit pulse checks to no more than 10 seconds. If a pulse is not clearly felt, resume compressions immediately. |

| Compression Fraction Goal | Aim for a compression fraction of at least 60% — meaning compressions are performed for at least 60% of total resuscitation time. Higher fractions (above 80%) are associated with improved outcomes. |

| Compressor Rotation | When multiple rescuers are available, switch compressors approximately every 2 minutes (or every 5 cycles of 30:2) to prevent fatigue and maintain compression quality. |

| Breaths Without Advanced Airway | When ventilating without an advanced airway, pause briefly to give two breaths, each lasting about one second, before resuming compressions. |

| Continuous Monitoring | Outside of advanced life support settings, pulse checks during active CPR are not supported by sufficient evidence and may unnecessarily interrupt compressions. |

Clinical Insight

The data are clear: minimizing interruptions saves lives. Chest compressions generate the blood flow that sustains vital organs during cardiac arrest, and each pause causes an immediate fall in perfusion pressure that takes several compressions to rebuild.

Healthcare providers should therefore strive for seamless transitions between compressions, ventilations, rhythm checks, and defibrillation — working as a coordinated team to ensure compressions remain continuous, deep, and fast, with minimal hands-off time.

Chest Compression Depth, Rate, and Recoil

High-quality CPR depends on maintaining the optimal compression rate, depth, and recoil, ensuring effective blood flow to vital organs. The 2025 AHA Guidelines reinforce these parameters as core components of resuscitation quality.

Key Metrics for Effective Compressions

| Focus Area | Best Practice Summary |

| Compression Depth | Compress the chest to a depth of at least 2 inches (5 cm) for an average adult, while avoiding depths greater than 2.4 inches (6 cm) to reduce the risk of injury. |

| Compression Rate | Maintain a steady rate of 100 to 120 compressions per minute — slower rates decrease perfusion, while faster rates may reduce depth and recoil. |

| Chest Recoil | Allow full recoil between compressions — rescuers should avoid leaning on the chest, enabling complete refilling of the heart and maintaining coronary perfusion pressure. |

| Compression/Relaxation Ratio | Aim for roughly equal time spent in compression and recoil phases to optimize forward blood flow. |

| Feedback Devices | Use real-time audiovisual feedback tools when available to monitor compression depth, rate, and recoil, helping rescuers adjust performance instantly. |

Clinical Insight

The effectiveness of CPR hinges on precise, consistent technique.

Compressions that are too shallow fail to generate adequate circulation, while those that are too deep can cause injury without additional benefit. Likewise, rapid compressions can compromise full chest recoil, reducing venous return and perfusion pressure.

Modern feedback-enabled defibrillators and training devices play an important role in maintaining performance — offering rescuers immediate guidance to ensure compressions remain within the ideal range of rate, depth, and recoil balance.

Ultimately, the AHA’s 2025 focus remains unchanged: every compression counts, and consistent, uninterrupted, high-quality chest compressions are the foundation of survival from cardiac arrest.

Fundamentals of Ventilation During Adult Cardiac Arrest

Ventilation remains a vital component of high-quality CPR, ensuring oxygen delivery and carbon dioxide removal during cardiac arrest. The 2025 AHA Guidelines reinforce the importance of providing adequate, controlled breaths that support perfusion without causing harm through hypoventilation or hyperventilation

Key Recommendations for Ventilation

| Focus Area | Best Practice Summary |

| Ventilation Method | In adults without an advanced airway, rescuers may ventilate via mouth-to-mouth, mouth-to-mask, or bag-mask techniques. |

| Tidal Volume | Deliver only enough air to produce visible chest rise — excessive volume can lead to gastric inflation or barotrauma. |

| Two-Rescuer Bag-Mask Technique | When using a bag-mask device, it is reasonable for one rescuer to maintain a two-handed mask seal while the second rescuer squeezes the bag, improving ventilation effectiveness. |

| Duration of Each Breath | Each ventilation should be delivered over approximately one second to allow gradual lung inflation. |

| Avoid hyper/hypo-ventilation | Rescuers must avoid both hypoventilation (too few or too small breaths) and hyperventilation (too frequent or excessive breaths), as both impair cardiac output and reduce survival. |

Clinical Insight

Providing proper ventilation during CPR — particularly without an advanced airway — is technically challenging. Air leaks, poor mask seals, or excessive pressure can result in ineffective oxygen delivery or gastric insufflation.

Because ventilation volume cannot be precisely measured during CPR, the best indicator of adequate ventilation is visible chest rise. Excessive ventilation (hyperventilation) is especially harmful, as it increases intrathoracic pressure, reducing venous return and cardiac output — ultimately decreasing the likelihood of ROSC.

The 2025 AHA evidence review reaffirms that balanced resuscitation — combining effective compressions with controlled ventilations — yields the best outcomes. This approach is particularly important when using the 30:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio, ensuring that at least half of the pauses in compressions result in successful lung inflation.

Ventilation During Adult Cardiac Arrest — Special Circumstances

The 2025 AHA Guidelines acknowledge that not every resuscitation scenario allows for standard mouth-to-mouth or bag-mask ventilation. In certain anatomical or pathological conditions, alternative ventilation routes may be required to ensure oxygen delivery.

Key Recommendations

| Special Situation | Best Practice Summary |

| Mouth-to-Nose Ventilation | If the patient’s mouth is injured, obstructed, or cannot be sealed effectively, it is reasonable for rescuers to provide mouth-to-nose breaths instead of mouth-to-mouth. This method can maintain adequate ventilation when oral access is limited. |

| Tracheal Stoma Ventilation | For adults with a tracheal stoma, rescuers may deliver breaths directly through the stoma, either by mouth-to-stoma or by using a face mask over the stoma. This ensures oxygenation when oral or nasal routes are not viable. |

Clinical Insight

Mouth-to-nose and stoma ventilation techniques are situational adaptations for unique airway challenges. The guiding principle remains the same — prioritize effective ventilation using any available route.

Rescuers must maintain a tight seal during these methods to prevent air leakage, especially when using bag-mask devices or face masks over a stoma. The AHA notes that management of surgical airways (e.g., tracheostomy tubes) extends beyond the scope of basic life support and should follow advanced airway management protocols when available.

Ventilation of Adults With Spontaneous Circulation (Respiratory Arrest)

The 2025 AHA Guidelines emphasize that prompt and effective ventilation is critical for patients who have a pulse but are not breathing normally. These individuals — often in respiratory arrest due to drug overdose, post-cardiac arrest states, or neurological compromise — require immediate assisted ventilation to prevent hypoxia and irreversible organ damage.

Key Recommendations

| Clinical Focus | Best Practice Summary |

| When to Ventilate | For adults with spontaneous circulation (palpable pulse) but absent or inadequate breathing, rescuers should initiate assisted ventilations without delay. |

| Ventilation Rate | Deliver 1 breath every 6 seconds (approximately 10 breaths per minute). Each breath should be just enough to produce visible chest rise. |

| Purpose | Maintain oxygenation and remove carbon dioxide to prevent hypoxic injury to vital organs such as the heart and brain. |

Clinical Insight

Respiratory arrest can quickly lead to severe hypoxemia — oxygen saturation may fall to dangerous levels within 90 seconds of apnea. Early, effective ventilation can rapidly restore oxygen levels and prevent deterioration into cardiac arrest.

Rescuers should focus on controlled, visible chest rise rather than excessive tidal volume or rate. This approach maintains oxygenation, reduces gastric insufflation, and preserves perfusion pressures.

These principles apply to post-ROSC patients and to non-cardiac causes of respiratory arrest, such as opioid overdose, underscoring the importance of early airway management and adequate ventilation in all resuscitation scenarios.

Compression-to-Ventilation Ratio in Adult Cardiac Arrest

The 2025 AHA Guidelines reaffirm that balancing chest compressions and ventilations remains a cornerstone of high-quality CPR. The goal is to maintain continuous circulation while ensuring adequate oxygen delivery — whether performed by a lay rescuer or a healthcare professional.

Key Recommendations

| Clinical Focus | Best Practice Summary |

| Standard Compression-to-Ventilation Ratio | Both lay rescuers and healthcare professionals should perform CPR using cycles of 30 compressions followed by 2 breaths (30:2) before an advanced airway is placed. |

| Alternative Approach (Healthcare Settings) | In certain clinical settings, healthcare professionals may consider continuous chest compressions with asynchronous ventilations, especially when a supraglottic or endotracheal airway is not yet available but additional rescuers are present. |

Clinical Insight

Two main strategies exist for adult CPR:

- Traditional 30:2 CPR — intermittent pauses for ventilation.

- Continuous compressions with asynchronous breaths — compressions continue while ventilations are delivered independently.

The 30:2 ratio remains the recommended standard for most situations, as it offers a proven balance between oxygenation and perfusion. However, in team-based resuscitation, when adequate manpower allows for coordination, asynchronous ventilation can maintain circulation with minimal interruption — particularly in extended resuscitation efforts or monitored healthcare environments.

In all cases, rescuers should prioritize minimizing pauses, maintaining a compression fraction above 60%, and ensuring each breath produces visible chest rise without delaying compressions.

Defibrillation During Adult Cardiac Arrest

Pad Placement and Technique

Defibrillation remains a critical link in the Chain of Survival, and correct pad placement is essential to ensure that electrical energy is delivered effectively to the heart. The 2025 AHA Guidelines provide updated recommendations that emphasize proper pad positioning, adequate contact, and sensitivity to patient privacy — especially during public or prehospital resuscitation.

Key Recommendations for Pad Placement

| Focus Area | Best Practice Summary |

| Pad Positioning | Place defibrillation pads or paddles directly on the bare chest in either the anterolateral or anteroposterior position. Both configurations are effective for adults in cardiac arrest. |

| Pad Size | Use large pads (≥8 cm in diameter) to reduce impedance and improve current flow through the myocardium. Larger pads are particularly appropriate for adult patients. |

| Skin Contact | Ensure direct contact with the skin; using pre-gelled pads or conductive gel helps optimize electrical conduction and minimize resistance. |

| Bra Adjustment (for Female Patients) | When defibrillating a female patient, it is acceptable to adjust the bra rather than fully remove it if doing so allows correct pad placement while maintaining patient dignity. |

Clinical Insight

Effective defibrillation depends on ensuring that the shock vector passes through the myocardium, particularly the left ventricle, where ventricular fibrillation (VF) commonly originates.

For anterolateral placement, rescuers must ensure that the lateral pad is positioned in the midaxillary line, not too far forward, to achieve optimal current flow.

The guideline also acknowledges a significant gender disparity in public access defibrillation — with women receiving defibrillation far less often than men, largely due to discomfort or hesitation in exposing the chest.

By encouraging pad adjustment instead of full removal of clothing, the AHA aims to reduce bystander reluctance and promote equitable access to life-saving defibrillation.

CPR Before Defibrillation in Adult Cardiac Arrest

Early defibrillation remains the most critical intervention for survival in adults experiencing ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT). The 2025 AHA Guidelines reinforce that while shocks should be delivered as quickly as possible, CPR should never be delayed while preparing the defibrillator or AED.

Key Recommendations

| Clinical Focus | Best Practice Summary |

| CPR Until Defibrillator Ready | Begin high-quality CPR immediately and continue until a defibrillator or AED is applied and ready to analyse or deliver a shock. |

| Unmonitored Arrests | In unwitnessed or unmonitored cardiac arrests, it is reasonable to perform a brief period of CPR while the defibrillator is being retrieved and prepared. |

| Immediate Defibrillation (Witnessed Arrests) | In witnessed or monitored VF/pVT arrests, where a defibrillator is already attached or immediately available, deliver the shock without delay. |

Clinical Insight

The timing of defibrillation is critical:

- Early shocks are most effective when VF/pVT has just begun, as the myocardium still retains sufficient energy reserves to respond.

- When the arrest has been prolonged or unmonitored, a short period of CPR (about 1–2 minutes) before defibrillation helps restore myocardial oxygenation and perfusion, improving the likelihood of a successful shock.

Equally important is minimizing perishock pauses — interruptions in compressions before and after defibrillation. Each pause causes a drop in coronary perfusion pressure, reducing the probability of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC).

In summary, the guiding principle is:

“Shock fast when you can, compress continuously when you can’t.”

Adult Foreign-Body Airway Obstruction (FBAO)

Foreign-body airway obstruction (FBAO) remains a preventable cause of respiratory arrest and death, most often resulting from food aspiration in adults. The 2025 AHA Guidelines provide clear, stepwise recommendations for identifying and managing both conscious and unconscious FBAO, including special circumstances such as pregnancy and obesity.

Classification and Recognition

FBAO is categorized as:

- Mild (Partial) Obstruction: The patient can cough, speak, or breathe, though with difficulty.

- Severe (Complete) Obstruction: The patient is unable to speak or breathe, may clutch their throat, turn cyanotic, and can rapidly lose consciousness.

Early recognition and prompt action are vital — the longer the obstruction persists, the higher the risk of hypoxic brain injury and death.

Management of Conscious Adults

| Clinical Situation | Recommended Intervention |

| Severe Obstruction | Perform repeated cycles of 5 back blows (slaps) followed by 5 abdominal thrusts until the object is expelled or the patient becomes unresponsive. |

| Mild Obstruction | Encourage the person to continue coughing to clear the airway while closely observing for progression to severe obstruction. |

| Emergency Activation | Call for emergency medical assistance immediately in all cases of suspected severe obstruction. |

Rationale: Early and coordinated action — especially by lay or first-response rescuers — greatly improves survival and neurological outcomes. Prompt EMS activation ensures access to advanced techniques and post-event monitoring, even if the obstruction is cleared.

Management of Unconscious Adults

Once a choking victim becomes unresponsive, the focus shifts to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR):

| Action Step | Clinical Guidance |

| Start CPR Immediately | Begin chest compressions without delay and activate the emergency response system if not already done. Compressions may help expel the obstruction by generating airway pressure. |

| Airway Inspection | After each compression cycle, open the airway and remove any visible obstruction only if it can be seen clearly. |

| Avoid Blind Finger Sweeps | Never perform a blind finger sweep — this may push the object deeper into the airway and worsen obstruction. |

Special Circumstances

Some situations make abdominal thrusts unsafe or impractical — such as in obese individuals, those in wheelchairs, or in the late stages of pregnancy.

| Scenario | Modified Technique |

| Obese or Wheelchair-Bound Patient | Use cycles of 5 back blows followed by 5 chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts. |

| Late Pregnancy | Perform back blows and chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts to prevent injury to the uterus and foetus. |

| Suction-Based Airway Clearance Devices | Evidence remains insufficient to support or oppose their use in adults. Further research is needed to establish safety and efficacy. |

Rationale: These modifications maintain airway clearance efforts while minimizing the risk of injury in patients where traditional abdominal thrusts cannot be performed effectively.

Key Takeaways

- Act fast: Delay in clearing obstruction leads to rapid hypoxia and cardiac arrest.

- Cycle methodically: 5 back blows → 5 thrusts → repeat until relief or unresponsiveness.

- Transition smoothly: Once unresponsive, move immediately to CPR with chest compressions.

- Modify for safety: Adapt techniques for pregnancy, obesity, or immobility.

- Never sweep blindly: Only remove an obstruction if it is clearly visible in the airway.

Cardiac Arrest in Adult Patients With Obesity

Obesity affects over 40% of adults and is a recognized risk factor for sudden cardiac arrest. The 2025 AHA Guidelines reaffirm that although CPR technique remains largely unchanged, rescuers must be aware of specific biomechanical and logistical challenges when managing obese patients in cardiac arrest.

Key Recommendations

| Clinical Focus | Guideline Summary |

| CPR Technique | Use the same compression and ventilation techniques as for non-obese adults. Standard hand placement, compression depth, and rate remain applicable. |

| Firm Surface Considerations | Rescuers should weigh the benefit of moving the patient to a firm surface (for effective compressions) against the risk of delaying CPR initiation. |

| Compression Force | Because of increased chest wall thickness, rescuers may need to apply greater force to achieve the recommended compression depth (at least 5 cm). |

| CPR Board Use | Using a partial backboard (CPR board) during in-hospital cardiac arrest does not improve outcomes compared to compressions performed on a hospital mattress. |

Clinical Insights

Performing high-quality CPR on obese patients can be physically demanding, often leading to faster rescuer fatigue and reduced compression depth over time. Rotating compressors frequently and using real-time feedback devices can help maintain compression quality.

Moving the patient should never delay CPR initiation — if the surface is soft (e.g., hospital bed), proceed immediately while optimizing compression technique. In cases of in-hospital arrest, firming the surface by adjusting the bed frame or inserting a backboard early may help, but only if it does not interrupt compressions.

Takeaway

- Same technique — adjusted effort: Compression depth and rate remain the same, but more force may be required.

- Prioritize continuity: Begin CPR where the patient is found; avoid delays for repositioning.

- Monitor rescuer fatigue: Rotate every 2 minutes to maintain performance.

- No proven benefit from CPR boards in obese in-hospital patients.

In essence: Effective CPR in obesity depends not on different methods — but on sustained depth, minimal interruptions, and coordinated teamwork.

Alternative Techniques for CPR in Adult Cardiac Arrest

While manual chest compressions remain the gold standard, the 2025 AHA Guidelines acknowledge that there are situations where conventional CPR delivery may be difficult or unsafe. In these instances, alternative approaches — such as mechanical devices or modified rescuer positioning — can be considered, provided interruptions in compressions are minimized.

Key Recommendations

| Technique / Setting | Guideline Summary |

| Mechanical CPR Devices | May be used only in specific situations where manual compressions are impractical or dangerous — such as during transport, in confined spaces, or when rescuer fatigue compromises quality. Interruptions must be minimized during deployment. |

| Over-the-Head Compressions | Single rescuers may consider performing compressions from above the patient’s head, particularly in tight spaces or during intubation. This allows access to the airway while maintaining compressions. |

| Heel or Foot Compressions | Evidence remains insufficient to support or refute the effectiveness of heel/foot compressions. These may be last-resort options in constrained environments. |

| Routine Mechanical Device Use | Not recommended for routine use in cardiac arrest — manual compressions remain superior when performed effectively. |

Clinical Context

Mechanical CPR devices generally fall into two categories:

- Load-distributing bands, which compress the thorax circumferentially.

- Piston-driven systems, which apply vertical compressions to the sternum.

While they can maintain consistent depth and rate, their setup time and risk of CPR interruption can offset potential benefits if not deployed by trained teams.

Over-the-head compressions are particularly useful for single rescuers or confined-space resuscitations (e.g., in ambulances or aircraft), allowing the provider to alternate between compressions and ventilation efficiently.

Heel or foot compressions have limited evidence and are only considered when manual hand compressions are not possible.

Takeaway

- Manual CPR remains the benchmark.

- Mechanical devices may serve as adjuncts in logistically complex or high-risk settings.

- Alternative rescuer positions (like over-the-head compressions) can enhance efficiency when manpower or space is limited.

- Training and proficiency are critical — these methods are only effective if applied correctly without interrupting compressions.

Why These Updates Matter

Each year, more than 356,000 out-of-hospital cardiac arrests occur in the U.S., yet survival remains near 10%.

The 2025 guidelines underscore that systems integration, quality improvement, and public access training are key to closing this gap.

By mastering these new evidence-based standards, healthcare providers can significantly enhance patient outcomes — both in-hospital and prehospital.

Learn the 2025 Guidelines — Get Certified in AHA BLS

Stay current with the American Heart Association’s latest resuscitation science and earn your international BLS certification through our accredited provider training.

Book Your Spot in the Basic Life Support (BLS) for Healthcare Providers Course — offered by the Health & Safety Training Centre of South Africa (HSTCSA).

This course covers:

- 2025 AHA BLS and ALS updates

- High-performance CPR and team dynamics

- Airway management and defibrillation

- Recognition and response to cardiac and respiratory arrest

Whether you’re a paramedic, nurse, doctor, or emergency responder, this course ensures your skills align with the latest international standards for saving lives.