BLS and ACLS Training Is Critical for Healthcare Professionals in SA

Cardiac arrest occurs across every level of the healthcare system, from high-acuity emergency units to general wards, outpatient departments, procedure rooms, and pre-hospital environments. Survival depends on the immediate actions of the clinicians present, and those actions must align with established standards of care. Basic life support training provides the foundation for those first critical interventions, while advanced cardiovascular life support training builds the structured decision-making required to manage complex arrest physiology and organised team responses.

For South African practitioners, these competencies are not discretionary. The Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) requires documented, current BLS proficiency for all registered professionals, and many clinical roles mandate additional training through an advanced cardiovascular life support course or recognised ACLS training pathway. These requirements exist because outdated or incomplete skills contribute directly to delays in recognition, interruptions in CPR, and incorrect sequencing of interventions—factors strongly associated with poor outcomes.

Healthcare facilities, legal bodies, and professional regulators evaluate clinician performance during cardiac arrest against recognised certification standards and AHA guidelines. Maintaining valid training is therefore a matter of patient safety, legal accountability, and professional compliance. In practice, clinicians with current BLS and ACLS training and certification are better equipped to deliver timely, coordinated care that aligns with both clinical evidence and regulatory expectations.

Read: The 2025 AHA Guidelines: Elevating Basic Life Support for Better Survival

Read: 2025 AHA Advanced Life Support Guidelines for Resuscitation

Minimum Standards of Care – What the HPCSA Expects

Regulatory Requirement

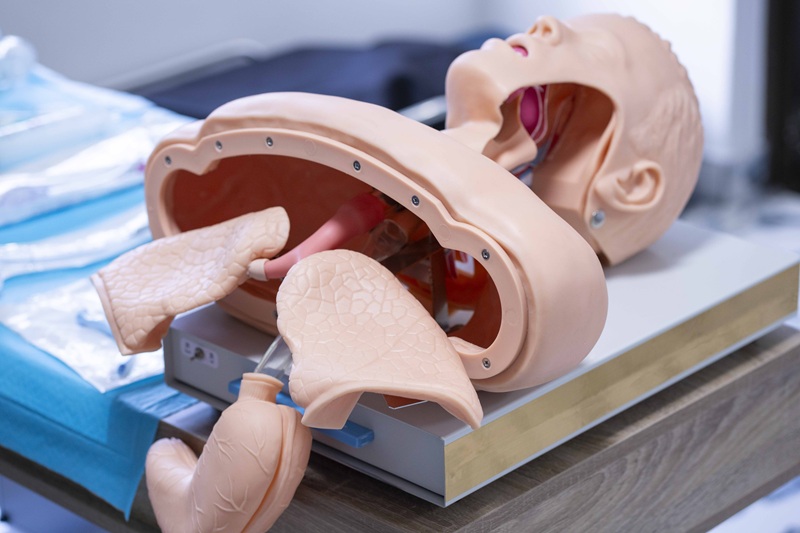

The HPCSA requires all registered practitioners to maintain current competence in basic life support. This obligation applies across all 12 Professional Boards and must be supported by documented completion of accredited, hands-on training. Online-only modules do not meet this requirement.

Why Formal Certification Matters

Accredited BLS provides a measurable standard of care. Hospitals and clinical services use this documentation to ensure that staff can perform the essential components of early cardiac arrest management, including:

- Immediate recognition of cardiac arrest

- Delivery of high-quality compressions

- Safe integration of defibrillation

- Coordination with the rest of the response team

This is the minimum expectation for any clinician involved in patient care.

Is ACLS Training Mandatory?

Certain environments require a higher level of competency due to the nature of patient risk. ACLS is routinely expected in:

- Emergency departments

- Intensive care units

- Operating theatres and procedural areas

- Anaesthetic services

- Advanced pre-hospital care

These areas depend on clinicians who can interpret rhythms accurately, prioritise interventions, and manage peri-arrest physiology without supervision.

Compliance and Accountability

Facilities must ensure that staff operate within established resuscitation standards. During internal reviews or external investigations, the absence of current BLS and ACLS training is treated as a deviation from expected practice. In these settings, certification is evidence that a practitioner meets the threshold for safe clinical participation.

Staying Current Prevents Skill Decay

Evolving Evidence

Resuscitation science shifts as new data becomes available. Adjustments to compression technique, ventilation strategy, drug sequencing, and defibrillation timing occur at regular intervals. These updates reflect measurable differences in survival and neurological outcomes. Up-to-date BLS and ACLS training that aligns with current guidelines ensures clinicians apply methods supported by the most recent evidence rather than outdated assumptions or habits formed years earlier.

Algorithm Familiarity

ACLS algorithms—whether for bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias, pulseless arrest, or peri-arrest instability—are designed to streamline clinical decision-making under pressure. Familiarity with these sequences is essential, not because the patterns are complex, but because hesitation leads to delays in treatment. Structured ACLS courses provide the repetition and context needed to apply these pathways reliably when time is limited and the clinical environment is noisy, crowded, or unstable.

Skill Degradation Over Time

Competence in CPR degrades rapidly without reinforcement. Studies consistently show that:

- Compression depth and rate drift outside recommended targets

- Ventilation volumes increase unintentionally

- Pause duration lengthens

- Rhythm recognition accuracy declines

This erosion begins within months of initial training. By the time a two-year renewal is due, unrefreshed skills often no longer meet the standard expected in clinical practice. Regular engagement with updated BLS and ACLS training and instruction stabilises performance and reduces variability between clinicians.

Operational Consequences

Outdated knowledge introduces avoidable errors during resuscitation. Examples include unnecessary pauses for rhythm analysis, incorrect defibrillation sequencing, and misinterpretation of non-perfusing rhythms. These deviations are routinely identified during morbidity and mortality reviews. Current training reduces the frequency of such errors and promotes consistent team behaviour across different departments and levels of experience.

Successful Resuscitation Depends on Team Performance

In cardiac arrest, the outcome hinges on how well the team functions, not on individual skill in isolation. A well-coordinated response requires each clinician to understand their role, recognise what others are doing, and anticipate the next required action. These elements break down quickly when training levels differ across the team.

One of the most common operational failures during an arrest is variability in technique. Compressions may not match guideline targets, ventilation timing drifts, or defibrillation sequences become disjointed. These inconsistencies create pauses, overlap of tasks, or gaps in care that accumulate into meaningful delays. Up-to–date BLS and ACLS training narrows this variation by standardising the behaviours expected from everyone participating in the code.

Teams with aligned training demonstrate several advantages:

- Less time spent negotiating who should perform which action

- Faster transition between tasks such as rhythm checks and defibrillation

- Clearer communication, particularly during high-stress moments

- Fewer unnecessary pauses in compressions

- More reliable adherence to the sequence of interventions

When even one clinician is uncertain or untrained, the entire workflow becomes unpredictable. Roles that should run in parallel collapse into sequential actions, costing time the patient cannot afford. Conversely, when the team shares a common educational foundation, coordination improves without the need for extensive verbal instruction.

This is why many units—especially emergency departments, ICUs, theatres, and advanced pre-hospital services—treat current BLS and ACLS training and credentials as operational requirements rather than optional qualifications. The goal is not merely to certify individuals; it is to ensure that the collective response is structured, deliberate, and consistent, regardless of who is on shift.

How BLS and ACLS Training Strengthen Clinical Operations Beyond Cardiac Arrest

BLS and ACLS competencies influence far more than the rare moments when a full resuscitation is required. Clinicians use components of these skill sets throughout routine patient care, often without identifying them as “resuscitation skills.” The result is a safer environment, earlier identification of deterioration, and more stable clinical workflows.

Early Recognition of Physiological Decline

Training sharpens a clinician’s ability to recognise subtle indicators of impending arrest. Changes in respiratory effort, progressive bradycardia, altered mental status, or irregular perfusion patterns become easier to identify when a clinician has reinforced the physiological framework that BLS and ACLS courses emphasise. This leads to earlier escalation and fewer preventable arrests.

More Accurate Assessment Under Pressure

Even outside a formal code, clinicians encounter moments where rapid evaluation matters. The structured approach taught in BLS and ACLS—Compression, Airway and breathing assessment without delay, targeted rhythm interpretation—translates into clearer thinking during chaotic or evolving situations. This improves the reliability of bedside decisions long before a cardiac arrest occurs.

Improved Use of Monitoring and Equipment

Training ensures clinicians can interpret monitor changes correctly, apply defibrillation pads safely, and recognise when device readings conflict with clinical presentation. These capabilities reduce equipment-related errors, which are more common in everyday practice than in formal resuscitations.

Reduced Variation in Patient Handover and Escalation

BLS and ACLS training promote a common clinical vocabulary. When clinicians communicate deterioration using standardised language—rate, rhythm, perfusion, work of breathing, responsiveness—the receiving team gains a clearer picture of the patient’s trajectory. This decreases the ambiguity that often delays escalation.

Stabilisation of Interdisciplinary Workflow

Units function more predictably when clinicians share an understanding of:

- When to call for help

- What immediate actions to take

- How to prioritise competing tasks

- When to avoid unnecessary interventions

This shared framework reduces the cognitive load across the team, especially during busy shifts, and prevents minor issues from escalating into emergencies.

A More Prepared Workforce

Hospitals with consistent training report smoother responses not only during arrests but also during near-arrests, rapid responses, sedation complications, and unexpected intra-procedural events. Staff are more comfortable stepping into defined roles, and junior clinicians integrate more quickly into high-acuity areas.

In this way, BLS and ACLS do more than shape the outcome of rare critical events. They refine daily clinical practice, strengthen early detection, and create more reliable systems across the entire continuum of care.

Why Both BLS and ACLS Training Are Necessary Rather Than Interchangeable

BLS and ACLS address different physiological problems, and neither can replace the other. Cardiac arrest demands two layers of intervention: one that maintains circulation in the absence of a functional heartbeat, and another that guides the clinical decisions required to restore organised electrical activity. These layers operate in sequence, not as substitutes.

BLS is centred on the mechanics of perfusion. Compressions generate forward blood flow, oxygen delivery depends on ventilation technique, and survival hinges on minimising pauses. Without these elements, there is no meaningful circulation for drugs to distribute, no perfusion for tissues to sustain, and no reliable rhythm to analyse. BLS provides the conditions under which any subsequent intervention has a chance of success.

ACLS enters the process only once those mechanical foundations are established. Its algorithms address rhythm identification, shock timing, medication sequencing, and the structured decision-making required to manage complex arrest physiology. These interventions do not compensate for poor compressions or ineffective ventilation; they assume those actions are already being performed correctly. When BLS quality is inadequate, ACLS interventions lose their clinical effect, even when applied precisely.

The skill sets also diverge in their focus. BLS emphasises physical technique and timing. ACLS emphasises interpretation, prioritisation, and the ability to redirect a failing resuscitation. Because they target different phases of the arrest response, maintaining competence in one does not imply competence in the other. A clinician may demonstrate strong algorithm knowledge yet struggle with the mechanics that determine whether those algorithms matter. Conversely, reliable BLS does not prepare someone to lead or sequence an advanced response.

For this reason, both forms of training remain essential. BLS sustains the patient long enough for advanced interventions to matter. ACLS provides the structure needed to convert a disorganised rhythm into a survivable one. The two are complementary, not hierarchical, and effective resuscitation depends on maintaining proficiency in each component separately.

HSTCSA – AHA Certified BLS and ACLS Training in South Africa

We provide American Heart Association–certified BLS and ACLS training designed for clinicians who require reliable, evidence-based instruction. Our courses follow the full AHA curriculum, include hands-on assessment, and meet the competency standards expected in South African hospitals and pre-hospital settings.

Training is delivered at our centre in Pinetown, KZN, with options for group sessions when departments need aligned proficiency.

If your certification is due for renewal or your unit requires accredited training that reflects current guidelines, you can book directly with us and secure your place in the next available course.

DISCLAIMER

This blog contains discussions and general information about medical emergencies and other health topics. The information in this blog and in other related resources is not meant to be medical advice, and it should not be taken as such. The information contained in this blog should not be used in place of a medical doctor’s advice or treatment. If you or someone else has a medical concern, you should talk to your doctor or seek out other professional medical care. The opinions and views on this blog and website have no connection to those of any school, hospital, medical facility, or other organization.