Why Are Paramedics Leaving South Africa?

Why Are Paramedics Leaving South Africa

DISCALIMER

This blog contains discussions and general information about medical emergencies and other health topics. The information on this blog and in other related resources is not meant to be medical advice, and it should not be taken as such. The information contained in this blog should not be used in place of a medical doctor’s advice or treatment. If you or someone else has a medical concern, you should talk to your doctor or seek out other professional medical care. The opinions and views on this blog and website have no connection to those of any school, hospital, medical facility, or other organization.

Introduction

There is an inexplicable passion that drives all who dare to enter the fast and furious world of emergency medical care. However, if you live in South Africa and want to be a paramedic, you’ll need to make sure that you’re able to afford the cost of training, continuing education, and the high- quality equipment that you need. Then you’ll have to consider your own personal security and the quality of life that the job will provide for you. These are some of the factors that play an important role in determining whether you’ll stay or go.

The shortage of ALS paramedics in South Africa is a serious problem. It is estimated that there are 1618 registered advanced life support paramedics in SA, which is far short of the global ratios. South African ALS paramedic migration falls into three categories. These are international, domestic, and special circumstances. Although these three types are distinct, they may share some common factors. Currently, there is little information available about the reasons behind ALS paramedics’ leaving South Africa. However, some studies have highlighted concerns. while others have proposed measures to improve staff retention. Hence, initiatives have been made to try and manage the shortage, such as accelerated training of entry-level staff to ALS. However, the measures seem inadequate.

This article will discuss the current registration levels, education and training, salary, working conditions, physical security and quality of life before concluding.

Current Registration Levels

In 2019, A study was conducted where the workforce composition was assessed. This was done using the professional registers held at the Health professions council of South Africa (HPCSA). This study found that In 2019, there were a total of 56 894 professionals who constituted the overall emergency care personnel registered with HPCSA. Of these, 10 545 were Ambulance Emergency Assistants (AEA’s), 43 045 Basic Ambulance Assistants (BAA’s), 705 Emergency care practitioners (ECP’s), 1123 Emergency Care Technicians (ECT’s) and 1476 ANT Paramedics, were recorded in the database until May 2019. (Tiwari et al. 2021). The study aimed to gauge the supply and status of human resources for EMS in South Africa. Researchers found that if current trends continue, there will be a shortage of around 96 000 emergency care personnel by 2030 (Tiwari et al. 2021).

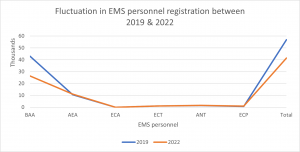

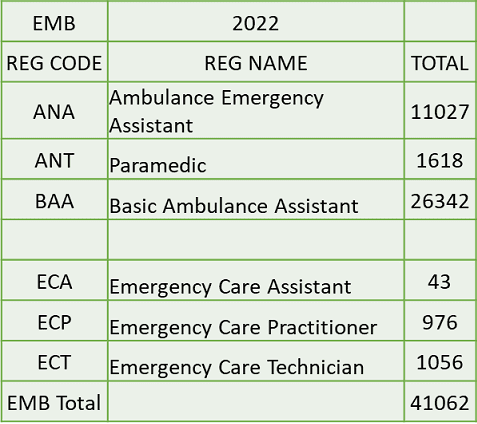

Figure 1: Describes the relative increase/decrease of registered personnel between 2019 and 2022

The graph above, illustrates a decrease in the total number of registered emergency care personnel to be 15 832 (28%). In 2019 The combined BAA and AEA cohort made up most of the registered emergency care personnel within the South African EMS. However, in 2022 we see that there is a 39% reduction in the registered BAA cohort combined with a slight 4.5% increase in AEA’s registering with the HPCSA. This trend is expected as the proposed closure of the BAA and AEA’s registers were finalised.

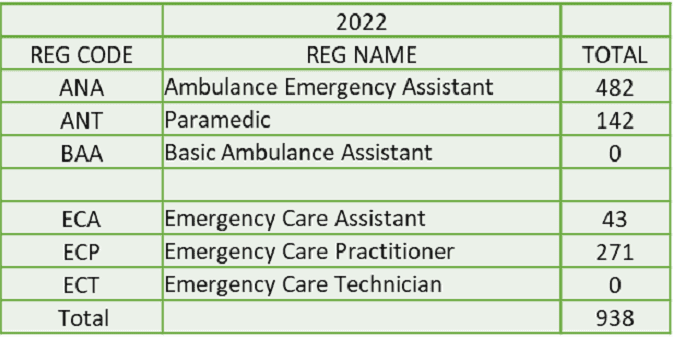

Figure 2: Emergency care personnel currently registered with the HPCSA as of 01 July 2022 compared to 2019

The growing concern among South Africans, is not having enough registered emergency care personnel to provide much-needed emergency medical care to the people of South Africa. The total number of emergency care personnel that is registered with the HPCSA between 2019 and 2022 is shown in this table. This roughly equates to approximately 312 emergency care personnel registering with the HPCSA per year.

It must be noted that, not all registered emergency care personnel practice within South Africa. Therefore, the actual number of emergency care personnel working within the South African EMS, may be way lower than what is illustrated in this table.

Education and Training

Ambulance services were primarily handled by South Africa’s municipal governments before 1970. Ambulance services are still used in place of fire and rescue departments in many communities. Municipal boundaries and apartheid homelands prevented people who resided beyond the town and city limits from entering, which also denied them access to emergency medical care in addition to suitable transportation to hospital. (National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2017)

Prior to 1994, the distribution of resources for ambulance services was based on race, with white individuals obtaining an unfair advantage. Organizations like St. John’s, the Red Cross, and The South African First Aid League played a critical role in many regions of the nation by filling in the gaps with ambulances staffed mostly by volunteers. Only a few of the larger cities had access to medical professionals who could treat and tend to the injured and seriously ill. As a result, the training and level of care offered were primarily restricted to first aid basics. (Sobuwa et al. 2019)

This dispersion of ambulance services can be attributed to the South Africa Act of 1909, which allocated hospital services and ambulance services to the three tiers of government. The subsequent State Health Plan and application of Section 16(b) of the Health Act, 1977 (Act 63 of 1977), however, excluded the former black homelands from responsibilities for providing ambulance services. (Sobuwa et al. 2019)

In the middle to late 1970s, a one-week basic ambulance course and a rescue medic course for staff members operating ambulances were first implemented. Then, under the direction of the South African College of Medicine, the pre-hospital emergency care committee created the Emergency Medical Assistant Course 1 for non-ambulance personnel. The Ambulance Medical Assistant Course 1 was introduced by ambulance departments. (Sobuwa et al. 2019)

The Ambulance Medical Assistant Course 2, which was later introduced, served as the foundation for the Critical Care Assistant (CCA) Course. These brief training sessions gave ambulance workers the skills they needed to operate under a doctor’s supervision. (Sobuwa et al. 2019)

The Ambulance Emergency Assistant (AEA) course, which lasted 12 weeks, the CCA course, which lasted four months, and the Basic Ambulance Assistant (BAA), which lasted three weeks, all began in 1985. Five more months of clinical roadwork was added to the CCA course. (Sobuwa et al. 2019)

It was recognized that in order to professionalize the industry and link the emergency care profession with other health professions across the country, professional credentials would be required. These credentials would be accepted, controlled, and registered by the HPCSA. The first of these credentials was a three-year national certificate that was made available in 1987 by Technikons (now known as universities of technology). By equipping graduates with the extra rescue skills, medical knowledge, and information required for them to work independently as pre-hospital emergency care providers, the three-year degree was designed to replace short-course training. (Sobuwa et al. 2019)

Following the democratically elected government’s election in 1994, nine new provinces, including the former black homelands, were established. As a result, the provinces’ allocation of resources was unfair. Because they need to cover more ground, emergency care providers must operate autonomously and provide clinical care of a higher calibre. This called for more sophisticated education. This takes the form of the Bachelor of Technology in Emergency Medical Care, which was introduced in 2001. (B. Tech EMC). The B Tech in EMC could be obtained by finishing two more years of part-time study after receiving the undergraduate three-year national diploma certification. (National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2017)

Under the leadership of the HPCSA, which functions as the Education and Training Quality Assurer (ETQA) and Standard Generating Body, the learning outcomes of the present short courses and higher education credentials underwent modifications between 2004 and 2006. (National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2017)

One outcome of this research and reorganization is the creation of a two-year, 240 credit NQF 5 Emergency Care Technician (ECT) qualification. This ECT program is regarded by the National Department of Health as being comparable to a “midlevel health worker” in the emergency care field. The emergency care programs offered by the appropriate higher education institutions’ three-year national diploma and one-year B Tech programs were examined. As a result of this evaluation, a four-year, 480-credit professional bachelor’s degree in emergency medical care was created

(B EMC). In 2005, a doctoral program and a master’s program were also established. (National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa, 2017)

The subsequent change in education and training with the aim of professionalizing the industry led to a two-fold problem that has contributed to the migration of emergency care personnel. On one hand, the lack of recognition of prior learning (RPL), distance learning, and online programs have greatly limited the ability of short course qualified personnel to access entry into the NQF aligned programs. As a result, many short-course qualified personnel have sought alternatives such as moving abroad or leaving the industry entirely.

On the other hand, the professionalization of the industry has also led to a unique situation where only a handful of universities and a few other organizations have the capacity to offer NQF-aligned programs. This has created a situation where a small number of emergency care personnel qualify annually. This has also resulted in a situation in which highly skilled graduates are either moving directly into management positions following graduation or are leaving the country in search of better opportunities.

Salary

Emergency medical service personnel are the first people who attend to accident victims and people who are sick or in need of emergency care. They figure out how sick the person is, provide life sustaining treatment, and transport patients to the hospital if needed. They then write a report about the care they have provided.

Most EMS personnel in South Africa earn lower salaries when compared to the international market. The average ambulance salary in South Africa is around R 240 000 per year, or R 123 per hour. For entry level positions, they earn about R 180 000 per year, while the most experienced workers can make up to R 469 795 per year.

The salary structure for EMS staff varies based on the employer, i.e., private or public sector. Salary structures also vary depending on the location, the number of years of experience, and the qualifications of the paramedics. Generally, salaries are higher in metropolitan areas than in rural locations.

A paramedic in Cape Town, for example, may earn slightly more than those in Johannesburg. This explains why the highest-paid paramedics work in the most populous city.

Paramedics also face high levels of burnout. Aside from a lack of adequate financial compensation, they face physical and emotional stress. Considering the nature of their work, many of them are reluctant to continue with the profession as their financial compensation is inadequate and cannot afford some of the services or activities that may be needed to assist in preventing burnout.

Working Conditions

In England and Wales It’s the first time since 1989 that ambulance workers have gone on strike, and there’s a good reason for that. Emergency medical services (EMS) are under pressure because of a shortage of trained personnel.

Emergency care is an important part of the health care system. It’s also considered a basic human right under the South African constitution. However, the working conditions for paramedics in South Africa and across the world have seemingly deteriorated.

Paramedics often complain about gruelling hours, a lack of compensation, disproportionate access to education and training, as well as a concern for their personal safety and security. One study lists the top five reasons for leaving operational practice as being related to “remuneration, a lack of control over workplace dynamics, inadequate opportunities for promotion, poor organizational communication, and poor benefits” (Hackland et al. 2011). While another study concluded that the data suggests that ALS paramedics in South Africa are leaving to find work outside the country because of working conditions, physical security, and economic considerations (Govender et al. 2012)

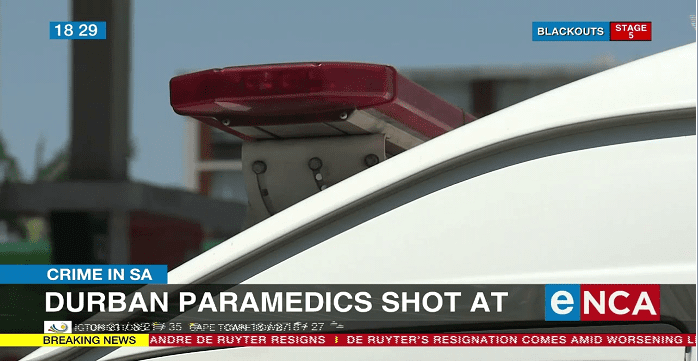

Physical Security

With the increasing crime rates, physical security is a major factor in the decision to leave the country. Criminals have now begun viewing EMS personnel as soft targets, and the number of attacks on EMS staff are on the rise. This is a huge concern for South Africa, as ALS paramedics have a host of global opportunities readily awaiting those who pursue this path. Some global recruiters do not even require professional registration of SA ALS paramedics in their host countries. In fact, they provide a multitude of global vacancies and flights.

Quality of Life

Paramedics leaving South Africa are mostly searching for a better quality of life which comes by receiving a better salary and benefits package. This has been an ongoing concern. Several studies have been conducted to address the issue, some providing suggestions to improve staff retention. And, while some initiatives have been implemented to help manage the shortage, it appears that current measures are insufficient to control migration of ALS paramedics from the country.

Conclusion

So why are paramedics leaving South Africa? Be what it may, this topic can be discussed for millennia, with different opinions expressed by different people. However, aside from the opinions, the fact is that South Africa is in a dire situation. According to estimates, if current trends continue, South Africa will face a shortage of approximately 96,000 emergency care personnel by the year 2030. The rate of brain drain does not appear to be slowing down. The end of an era of short courses and the realignment of prehospital education and training with an aim to professionalize the industry have resulted in a mass exodus of emergency care personnel. This, combined with low salaries in relation to the international market, questionable working conditions, increasing crime rates, and threats to personal security, has made many South African paramedics question their place within the industry. The promise of “greener pastures” by international organizations has also drastically reduced South Africa’s ability to retain highly skilled and internationally sought-after staff. If the public and private sectors continue to ignore the obvious reasons why paramedics are leaving South Africa, there may soon be no emergency services available to the people of South Africa.

References

Tiwari, R., Naidoo, R., English, R. & Chikte, U. (2021) ‘Estimating the emergency care workforce in South Africa’, African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 13(1), pp. e1-e9. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.3174

Govender, Kevin, et al. “Developing Retention and Return Strategies for South African Advanced Life Support Paramedics: A Qualitative Study.” – ScienceDirect, 25 Dec. 2012, sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211419X12001206#s0075 www.mindmuzik.tech. “Publications – HPCSA.” Publications – HPCSA, www.hpcsa.co.za/?contentId=305&menuSubId=0&actionName=Publications. Accessed 24 Dec. 2022.

Govender, Kevin, et al. “The Pending Loss of Advanced Life Support Paramedics in South Africa” – ScienceDirect, Dec. 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2011.11.001

Hackland, Stuart, and Christopher Stein. “Factors Influencing the Departure of South African Advanced Life Support Paramedics From Pre-hospital Operational Practice.” – ScienceDirect, 29 July 2011, sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211419X11000413.

Sobuwa, Simpiwe, and Lloyd Denzil Christopher. “Emergency Care Education in South Africa: Past, Present and Future.” Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, vol. 16, Australasian College of Paramedicine, Mar. 2019. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.16.647

“MEDBOX | South Africa: National Emergency Care Education and Training Policy.” MEDBOX | South Africa: National Emergency Care Education and Training Policy, Accessed 24 Dec. 2022.medbox.org/document/south-africa-national-emergency-care-education-and-training-policy#GO

About the Author

Hello, I’m Ryshane Sewpersad, a seasoned emergency care practitioner with over 15 years of experience across national and international settings. Registered with the Health Professions Council of South Africa and various international bodies, my career spans significant contributions to emergency medical services through course development and the establishment of clinical practice guidelines. My commitment extends to providing quality education and training in the field. An avid adventurer at heart, I am continually in pursuit of new challenges

Responses